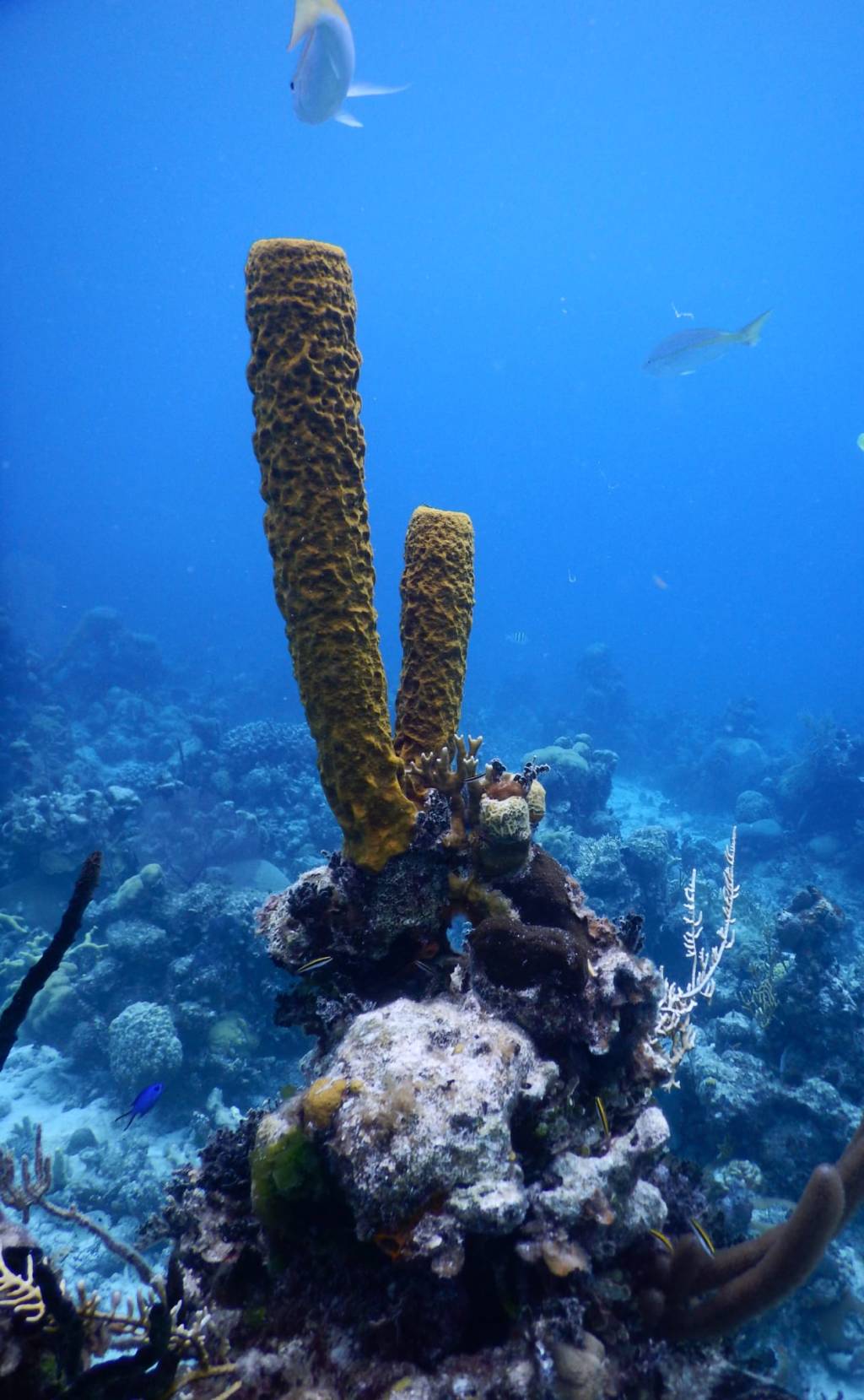

Plunging into that tropical sea was like climbing down the ladder to a different world, one cut off by a portal of waves and sunlight. The coral reef was a carnival of life, a dream of colour combinations that broke the rulebook of art. Sea fans waved back and forth with the pulse of the water. Fish played hide and seek amongst the ethereal coral, a scattered, dazzling kaleidoscope of colour – vivid purples, yellows and blues.

Fifteen metres down… Twenty metres…

I sucked in cold, industrial air through my respirator. With every breath, thick pillars of silvery bubbles wafted to the surface. My breathing apparatus was my life-line, a tool which allowed me to survive momentarily in a world in which I do not belong. My buoyancy control device kept me stationary in the water, enabling me to defy both gravity and the forces pulling me to the surface. Reaching my maximum depth, I looked towards the direction from which we came. The reef gradually sloped upwards towards the coast, the water getting increasingly shallower and lighter. In the opposite direction the coral abruptly ended, with the seafloor sloping into a dark stout-coloured abyss. This area is known as ‘the drop off’, where the relatively shallow coral shoreline meets the open water of the bay, which can be eight-hundred feet deep in some places.

About thirty minutes in, I looked at my air gauge, a flimsy piece of metal dangling around my waist. The needle hovered perilously over the word ‘EMPTY’ etched on the far-left side. My breathing apparatus was almost out. At that depth, racing to the surface to catch a breath was unthinkable. One of the golden rules of SCUBA diving is never to ascend or descend too quickly. It can result in decompression sickness (‘the bends’), a nasty build-up of nitrogen in the tissues which can cause paralysis and death.

As part of my training, I was taught for events such as this. However at the time, preparing for such emergencies feels about as useful as a flight attendant’s safety demonstration – one of those things you have to listen to, but know you will never need. But today I did. Placing the palm of my hand facing down, I simulated a slice movement near my neck, signalising to my dive partner that my tank was out of air. I then placed my flattened hand on my own mouth and moved it back and forward in an exaggerated motion one might do when covering a yawn. My dive buddy opened her arms, allowing me to take her second respirator and breathe from it. We slowly ascended to the surface, the sunlight reaching for me down the water column and drawing me up like a pair of arms.

I was very glad to finally make it to the shore. To my embarrassment, the incident had not been due to a fault in our hired equipment. I had in fact forgotten to tighten a certain valve, so the air had slowly been seeping out like a punctured inflatable. After this mild embarrassment, I was not sure which was more deflated – the air cylinder or my ego.

Aged fifteen, I joined ‘Operation Wallacea’, a research expedition based in the Bay of Pigs, Cuba. Our mission was to gather data on forest and coral reef ecology for studies being conducted by scientists at the University of Havana. The information we hoped to gain would shed light on the health of the Cuba’s natural spaces, and in particular, how successful conservation efforts had been. The area where we were staying was adjacent to the Zapata Swamp National Park, an internationally recognised area of biodiversity and the largest wetland in the Caribbean. In my previous post, I detailed my exploration of the forest, where I saw an array of rare and endemic species, including the critically endangered Cuban crocodile. You can read my first article about this expedition here.

Whilst the swamps, mangroves and forests of the area are known for their abundance of wildlife, the coast is also a nature hotspot. The Bay of Pigs is home to miles of azure water, golden sand beaches and spectacular coral reefs. Our particular area of interest was Punta Perdiz, a dive site located on the east coast of the bay. Each morning, we took a bus from Playa Girón, where we were staying, to Perdiz. The bus was old and rickety, probably from the 1950s or ’60s. It had a maximum speed of about forty miles per hour and billowed out factory-level amounts of smoke. I thought to myself of the humorous irony: we visited the dive site to help protect the environment, all the while riding a bus spewing pollution into the air.

The reef was a beautiful metropolis of sea life. I spent many mornings stood on the beach, the sun glaring down through thick whisps of white cloud. Coral formations were easily distinguishable even from the shore, appearing biro blue in contrast to the lighter turquoise backdrop of the sandy water. But the only way to truly appreciate the reef’s grandeur was by diving. Staggering clumsily across the beach, weighed down by a SCUBA suit as heavy as chainmail, we would immerse ourselves in the water (which was as warm as the air). After treading 50 metres or so out to sea, we would descend, blowing a net of bubbles in our wake like smoke chimneys. As the water pressure built, it was important to ‘equalise’ your senses. This was done by holding your nose while squeezing your sinuses.

Venomous invaders

As incredible an experience the diving was, it was not all leisure; we did have a serious task at hand. One of our main conservation goals was to cull the highly venomous red lionfish. These fish have been wreaking havoc across the Caribbean. Originally from the Indo-Pacific, lionfish were introduced to the Caribbean in the late 1900s, most likely through deliberate release from the aquarium trade. The descendants of these released fish have since established huge populations across the Caribbean Sea, up north towards the coasts of Florida and the Carolinas, USA. They have even recently been sighted as south as the coast of Brazil.

Their rapid spread is a real threat. Lionfish have no natural predators in this part of the world, and prey on more than seventy marine fish and invertebrate species. In addition, they threaten the coral reef itself, not just its inhabitants. As well as reducing the amount of native fish in the reef, lionfish also indirectly cause excessive and harmful algal growth on coral reefs. This is because they eat herbivores, which themselves keep the coral clear of algae.

Various efforts, however, are underway to try and tackle this ecological disaster. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission runs the ‘Lionfish Challenge’, an annual competition to incentivise fishermen and divers to catch as many lionfish as possible. Elsewhere, articles titled ‘Save a reef, Eat a lionfish’, or similar, are appearing more and more online. Once the venomous spines have been removed, the fish is said to be a tasty meal. The hope is that if the demand for lionfish becomes commercially high enough within the Caribbean seafood market, commercial fisherman will have an incentive to start hunting them. During our expedition, several were caught.

This raises an important point about conservation. It is a widely held presumption that wildlife protection intrinsically involves preserving all types of life. To many, killing animals is the antithesis of what wildlife conservation should look like. But in a brutal twist of irony, killing these particular fish is actually a crucial means to conserving reef biodiversity. By controlling lionfish populations in areas they do not naturally belong, more vulnerable native wildlife will have a chance to prevail.

This same phenomenon exists throughout the world. In the UK alone, grey squirrels are an invasive species, having been brought over from America. Their presence has driven out the native red squirrels from almost all of England. Whilst, much to the relief of the UK public, park keepers in London are not going around Hyde or Greenwich Park with spears and impaling squirrels, the threat they pose to the natural ecosystem is very much the same.

Recording the Reef

Another conservation task was to record videos of certain areas of the reef. By watching this footage back on shore, researchers would then be able to assess the abundance, variety and distribution of different reef species.

- Abundance – The number of individuals of a particular species within a defined area or habitat.

- Variety – The diversity of species present within a given area or habitat. Divided into two areas:

- Species Richness: The total number of different species present within a given area. For example, a coral reef with 40 species of fish would have a higher species richness than one with only 20.

- Species Evenness: This is a measure of how evenly the individuals are distributed among the different species. A community where each species has a similar number of individuals has high species evenness. If some species dominate over less abundant ones, the area has low species evenness.

- Distribution – How individuals in a population are distributed in a given area. Organisms making up a population may be more or less equally spaced, clustered in groups, or dispersed randomly with no pattern.

We filmed the reef using two main techniques:

LIT (Line Intercept Transect)

This method is used to assess the composition and health of a coral reef. It works in the following ways:

Setup: A transect line is laid down on the reef by divers. This is typically a harmless material, such as a tape measure, that will extend for a given distance (typically ranging from ten to fifty metres).

Sampling and measurements: Divers swim slowly from one end of this line to the other, steadily recording the coral in front of them with an underwater camera.

Analysis: The gathered data can provide insights into the overall health of the coral community in a surveyed area. If plenty of transect surveys are done in a given reef location, scientists can extrapolate the data to estimate the overall health of the area, as discussed further below.

Quadrat sampling

Like the LIT transect, an underwater camera is used to film a given area. However instead of a tape measure line, a square frame (usually 1×1 metre) is placed on the area. Locations may be chosen at random, or based on specific criteria, such as different reef zones or depths. Within each quadrat, researchers view the recorded footage to identify the types of corals visible, along with their health, size and condition. This method is used to estimate the overall abundance and distribution of organisms in a given area. It should be noted that this method is widely used throughout ecology in a range of habitats, such as in fields.

Streamlining science: extrapolation

For both techniques, by taking several measurements from different areas of the reef, the data can be extrapolated to estimate the overall biodiversity of a much larger area, such as an entire reef formation. This saves scientists a huge amount of time and money, and is a reliable way of building a picture of the entire habitat’s health in a given area without filming every square metre in an area that may be many square miles across. Whilst the data is only an estimate, this method saves time and money.

Both techniques are standardised, meaning that they are done in exactly the same way whenever of wherever they are carried out. As a result, they are useful for monitoring changes in a given reef over time, or for comparing different coral locations.

Threats to the Reef

It would be easy to disregard the corals, stone-like in their immovability, as being lifeless and senseless. Despite common assumptions otherwise, corals are animals. As discussed with regard to the lionfish, coral reefs are home to fierce interspecific competition (conflict between different species). The corals themselves also face a range of threats:

- Climate change – Warmer sea waters can lead to coral bleaching, caused by the corals expelling algae from within their tissues. This causes them to turn white, and will eventually lead to death. Throughout the world, these once beautiful mosaics of colour are slowly turning ashen, like some dystopian aftermath of a bomb. When the colour goes, so too do the reef fish and other wildlife.

- Ocean acidification – This is correlated with the increased carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere. As the ocean absorbs carbon dioxide, the resultant decrease in pH weakens the corals by preventing them from being able to build strong calcium carbonate skeletons.

- Pollution – This is a particularly serious problem near agricultural areas, where harmful chemicals may enter the water. Litter is also a huge problem. It has been estimated that more than one million sea turtles die every year due to ingesting plastic.1

- Overfishing – This problem is not limited to just coral seas, however reefs are particularly sensitive to such changes in biodiversity. Not only are industrial fishing practices unsustainable, they also result in bycatch – the unintentional killing of species that are not wanted by the fishing fleet. Each year, millions of fish, turtles and other marine animals are caught in huge nets that were not intended for them.

- Invasive species – Such as the lionfish.

- Harmful tourism – The reef should be enjoyed by visitors, and tourism can bring in huge amounts of money for local communities. In an impoverished country such as Cuba, this is vital. However trampling or anchoring on the reef can damage corals, as can excessive amounts of harmful sun cream being added to the water. With many coral reefs being located in less economically developed countries, tourism should be managed in a way that benefits the host country without harming the environment.

Throughout my series of dives, we saw a dazzling array of species. These included the batfish, which crawls around the seafloor using its fins. We also saw the sergeant major fish, unmistakable with its bright blue and yellow stripes. Perhaps most striking of all was the stoplight parrotfish, with its shiny turquoise, yellow and purple scales. Incredibly, this species changes its sex from female to male during its lifespan. Most exciting of all, however, was the green sea turtle. This elegant figure caught my eye as we ascended from the reef during a return to the shore, the leathery textures of its shell glowing in the sunlight. It moved purposefully and elegantly through the water, flapping its fin up and down like the rising and falling waves on the shore. Encounters such as this reminded me of the importance of our expedition. The love of nature, after all, is the greatest incentive to protect it.

Leave a comment