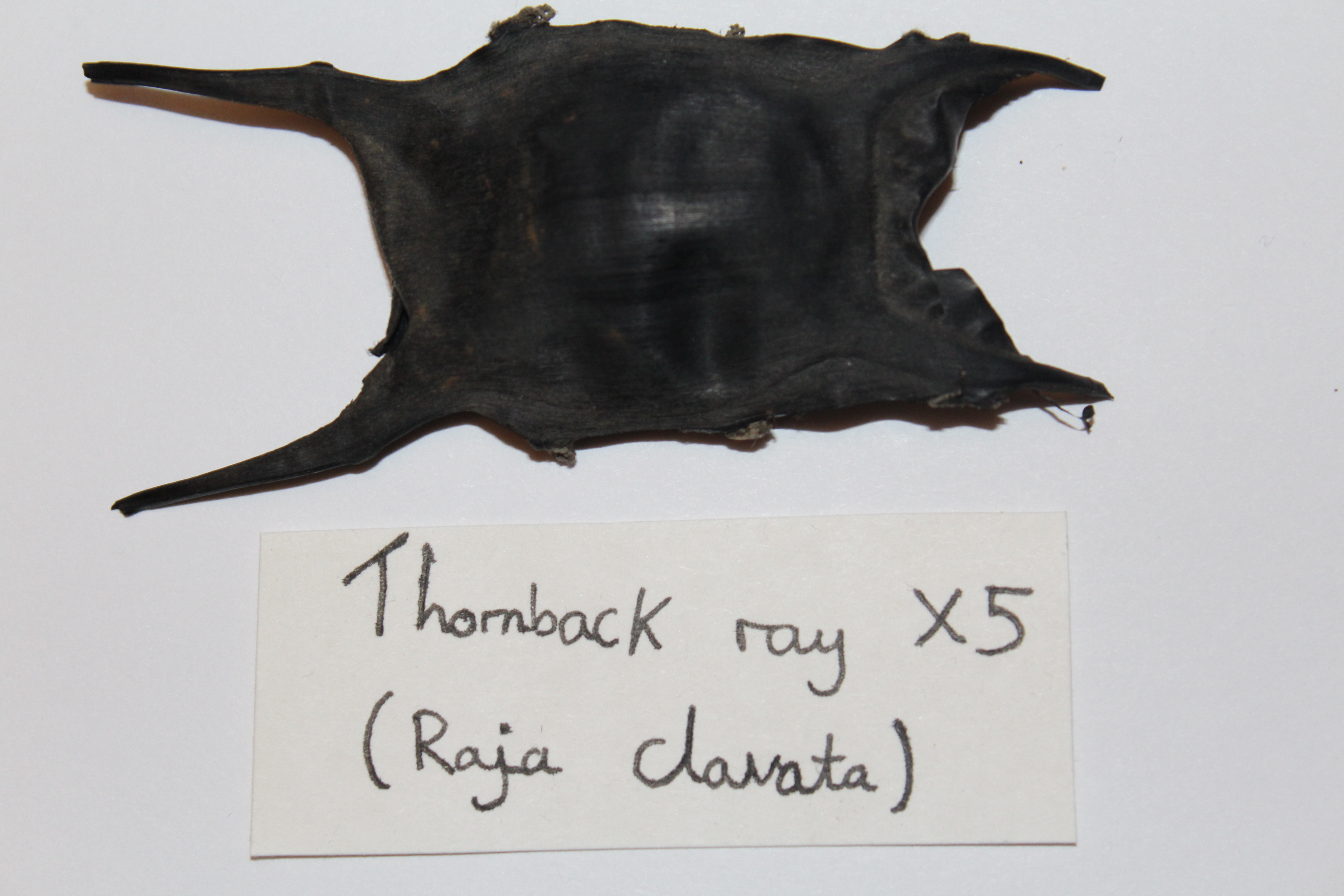

They may look like a washed up piece of seaweed, but egg cases are a wonderful indicator of just how rich our oceans are. Sometimes referred to as ‘mermaid’s purses’, egg cases are the protective shells which house the developing embryos of some cartilaginous fish – sharks, skates and rays. They are typically palm-sized, rectangular in shape, and have a plastic-like exterior. Tendril-like extensions in the corners anchor them to a surface (such as the seabed) and prevent the egg from being swept away. Much like a hatching bird chick, a fully developed fish embryo will emerge from its safe haven and join the sea.

From the shore, it can be easy to disregard our British oceans as being barren and biologically quiet. Where I live (near the Thames Estuary), the sea is a murky green colour thanks to the regular churning of sediment. We rarely have marine mammals, and any fish nearby are invisible in the poor visibility of the water. For many, the only sight of a British fish they will ever have is at the fishmonger aisle of a supermarket.

But the great thing about egg cases is that they make the presence of wild fish species accessible and tangible for ordinary folk. You don’t need to get into a wetsuit or board a boat to see these signs of marine life. They appear everywhere along the UK coastline (we have 11,073 miles of it). Dog walkers, beach-combers, indeed anybody walking along the shoreline can see them. What makes them particularly special is that they indicate the diversity and populations of different fish species living in our waters, even if we never get to see those fish.

The Great Eggcase Hunt

In previous articles, I’ve discussed collecting and identifying various egg cases which I found washed up on the Kent coastline. Among these writings were my ‘top tips for egg case hunting’, a rudimentary but useful article I wrote when I was thirteen (2015). My findings were recorded and added to the ‘Great Eggcase Hunt’, a citizen science project run by the UK charity Shark Trust. This scheme encourages people who find egg cases to identify which species produced them, and log the location of their finding. It has now attracted attention from around the world, with sightings and recordings even being given from Australia.

Getting started

The project’s website features an identification guide for recorders to ascertain which species their egg case belongs to. After identifying, recorders can then pinpoint on a map where they found the egg case, and declare which species it is. This simple and easy-to-follow method has resulted in an enormous data set of the populations and distributions of oviparous cartilaginous fish around our coast.1 By knowing which species are present around which parts of our coastline, conservationists are better able to determine if populations are changing. Citizen science projects such as this not only enable charities to gather useful data, free-of-charge, but are a great way to educate and engage the public. This isn’t my first experience with marine data collection projects, however. I’ve previously submitted my jellyfish sightings to the Marine Conservation Society. My most exciting encounter with a marine stinger was explored in my article on a Portuguese man of war sighting in Cornwall, which at the time was mentioned in BBC Wildlife Magazine.

Using their jellyfish data, the MCS tracked changes in jellyfish numbers and distribution. For instance, after the 2022 heatwave, they reported a 32% rise in jellyfish numbers.2 As our ocean’s warm in accordance with climate change, we are also starting to see species that were previously limited to warmer waters, such as crystal jellyfish, turn up here in the UK. This could be due to what University of Plymouth academic Dr Abigail McQuatters-Gollop refers to as a ‘tropicalisation of the oceans’ due to climate change. Such scientific hypotheses wouldn’t be as easy to come by without the vast data provided by ‘citizen science’, as it is known.

Egg case hotspots

The map below was taken from The Shark Trust’s 2023 Annual Report. Egg case hotspots included the Lancashire coast, the South Coast and the South East.

As with any set of data, it is important to take into consideration any factors and variables that could affect the results. For instance, these ‘hotspot’ areas are also densely populated, so the high numbers of recordings may not necessarily mean that elasmobranch populations are highest here, but may simply reflect the popularity of these beaches and subsequent higher frequency of sightings. Similarly, the lack of sightings around Scotland and Ireland doesn’t automatically mean these areas don’t have cartilaginous fish living in their waters, as these areas are sparsely populated.

However, this population density trend doesn’t always follow. A particularly striking example why is the coastline around the Orkney Islands. This area is sparsely populated, yet saw plenty of recordings.

One of the drawbacks of this method of data collection is seasonality. Not only do fewer people visit the coastline in the winter, but their interaction with the coast will make them less likely to find egg cases. Whereas summer visitors will sit in close proximity to the tide line (thereby more likely to see egg cases), winter visitors tend to walk further from the shore.

Aside from mere population density, a further factor at play is the social variation between different coastal areas. Hotspots such as the South Coast, the South West and the coastline of Wales are also popular tourist areas. The types visiting these areas, such as families, are more likely to be interested in and aware of the ‘Great Eggcase Hunt’. The name of the project itself sounds very child-oriented.

The Case for Citizen Science

In an era where our oceans are facing serious threats, quantitative data gained from citizen science projects can be an important tool to win the hearts and minds of both politicians and the public. Numbers and graphs tend to be far more effective than words and abstract ideas in persuading readers. This what leads to impactful change, such as the creation of no-fishing zones, reducing ocean litter or limiting dredging. By gaining valuable data not from nerds in lab coats, but from citizens themselves, these projects may be crucial in bringing about the changes that will protect our seas.

- Not all cartilaginous fish (also known as elasmobranchs – sharks, skates, rays and chimaeras) are egg-laying. Most species of sharks, especially the larger ones, give birth to live young. The egg cases seen in the UK tend to be of small elasmobranchs, such as rays. ↩︎

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-67301074 ↩︎

Leave a comment